What about Sex Education in Italy? The latest Italian bill and what a sex education program should contain today

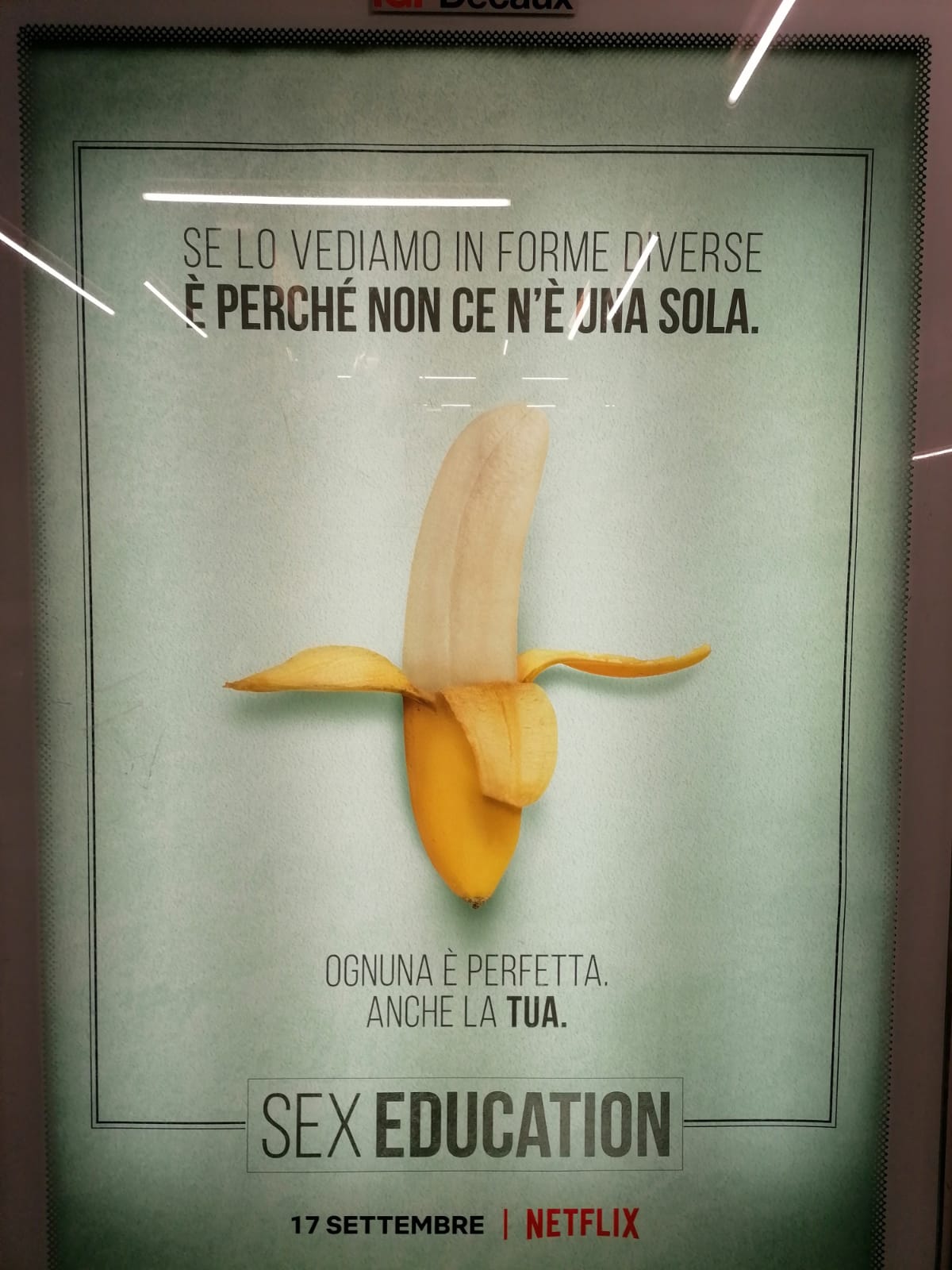

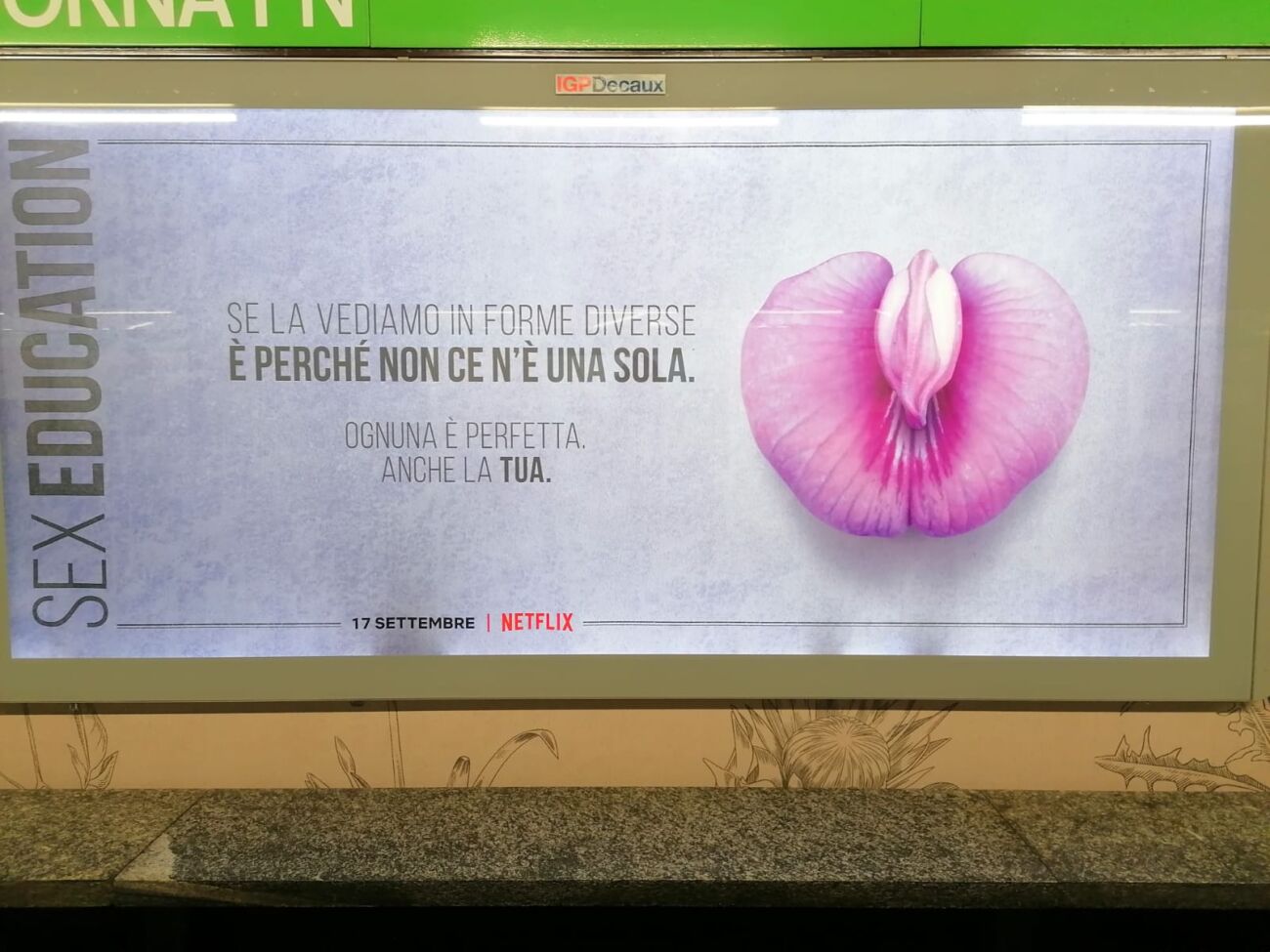

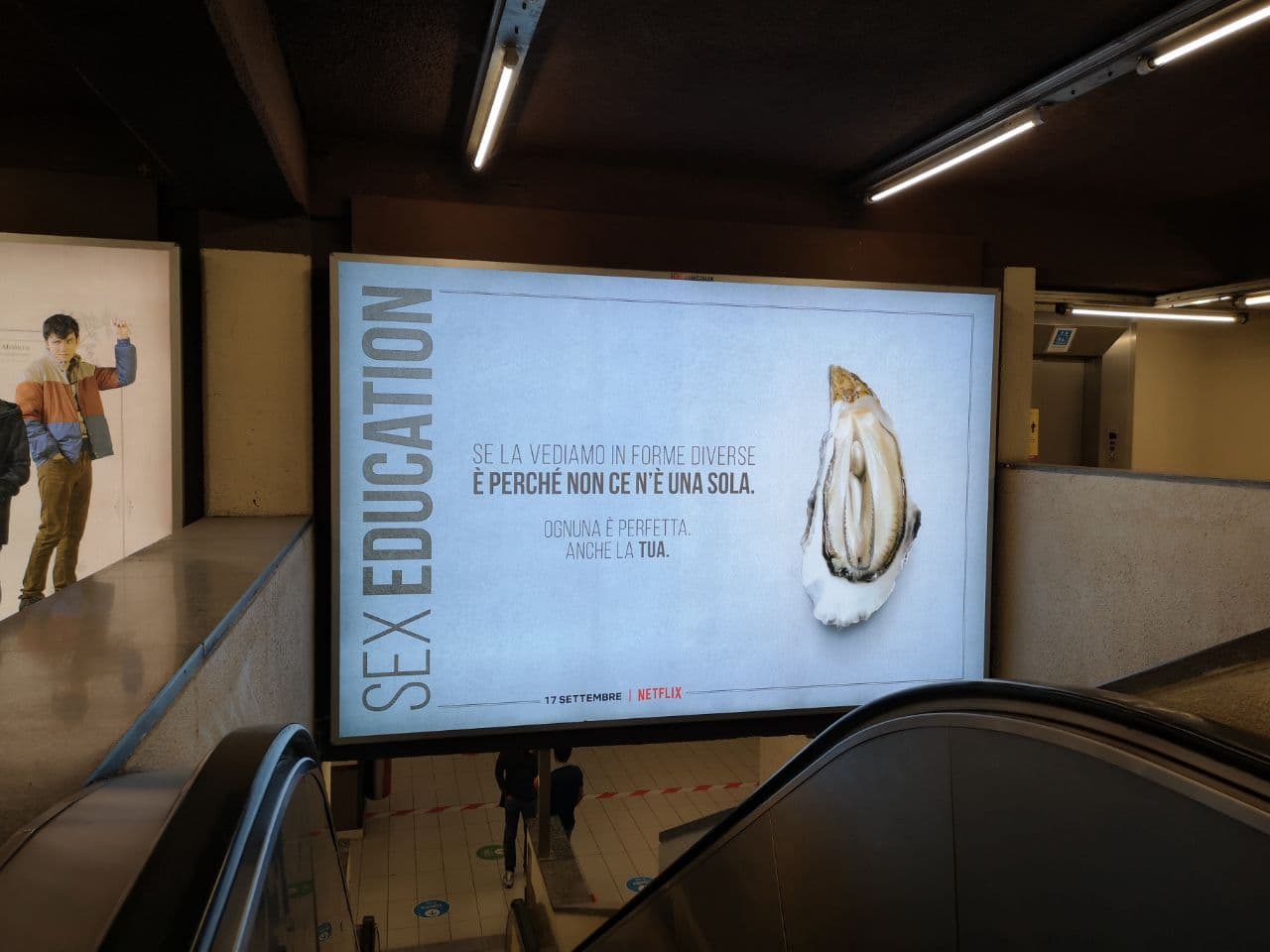

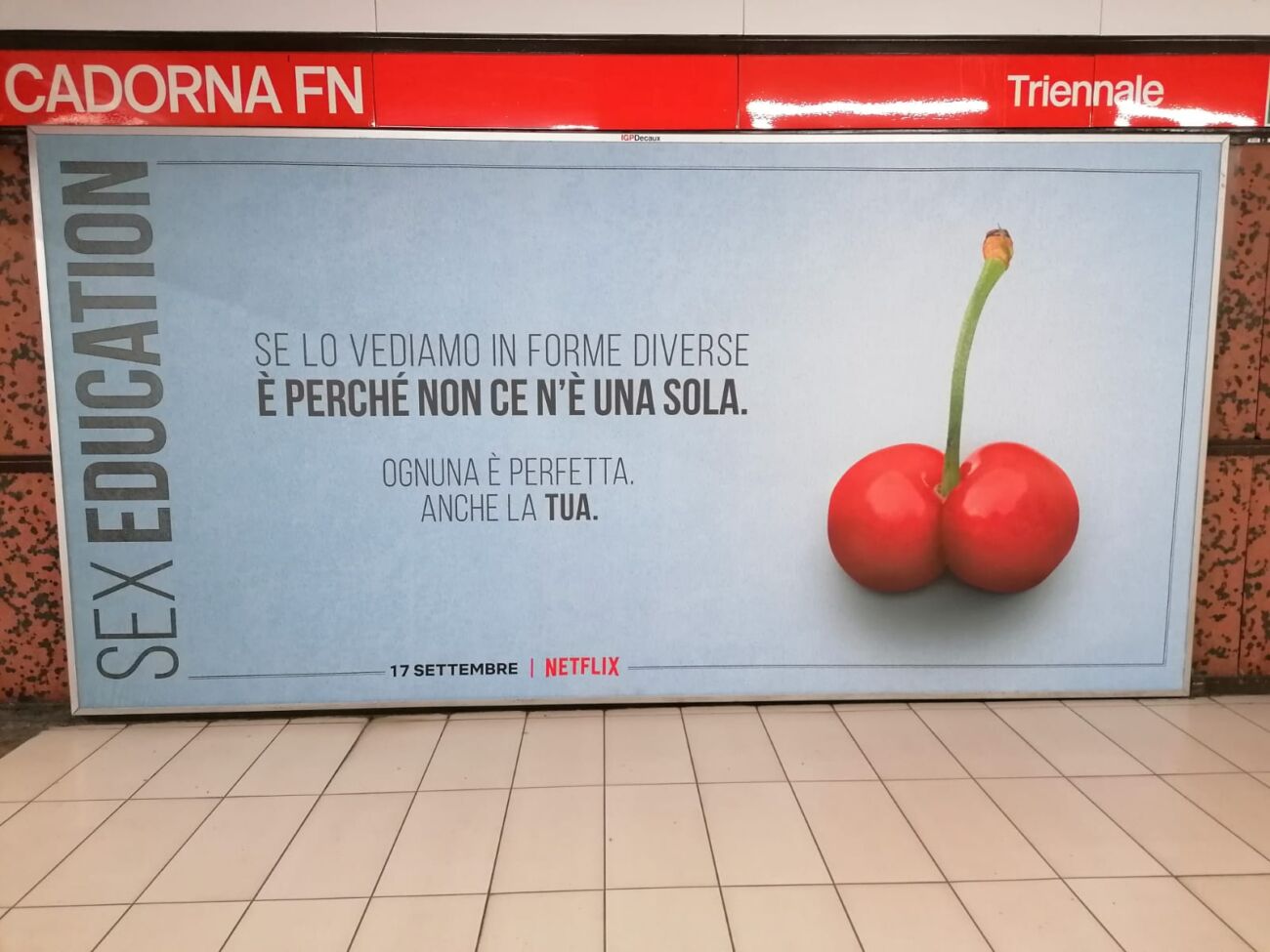

For the release of the third season of Sex Education, Netflix's acclaimed TV series and sex positive teen drama, Milan was carpeted with commercials featuring images of plants, flowers, fruit and vegetables that represented the variety of shapes, sizes and colors of the sexual organs: «If we see it in different forms it is because there is not only one. Each is perfect. Yours too». Let's make a very brief overview for those who haven't seen it: the series tells the story of a British school - in a very American retro 80s scenographic mood - where Otis, the protagonist, also son of a sex therapist, begins to give sex-education advice to his schoolmates. In the series there is a girl, Aimee, who after suffering an episode of sexual violence turns to Jean, the sexologist played by Gillian Anderson, to reconnect with her intimacy. Returning to the campaign, in the third episode of season 3 the issues of embarrassment and disinformation surrounding the genitals are addressed, and Jean advises Aimee to look at the site all-vulvas-are-beautiful.com to get an idea of the multiple existing differences.

Netflix, among other things, has developed that site in collaboration with The Vulva Gallery, another campaign for Sex Education which, if on the one hand it is a product that wants to satisfy the sympathies of the target, on the other it is also a reminder of how much the GenZ feels the need for sex education.

This request, however, has not been perceived by some areas of Italian politics, and according to them the posters hung by Netflix should be removed as "obscene content”. Among the controversies there is that of Barbara Mazzali, regional councilor of Lombardy with Fratelli D’Italia party: "Is it acceptable that such posters are there for everyone to see, including children? Sex education must be in the hands of the family”. This is the favorite slogan of the conservative currents who, in 2021, do not realize that yes, the idea is that everyone, regardless of age, can have access to these posters, because no, the family can’t be the the only place dedicated to teaching these topics, for a simple reason: it does not have all the necessary skills.

Why it is important to have sex education in school

In recent decades, it has been understood that having a school sex education program can have a positive effect on broader social issues such as gender equality, human rights and general wellbeing. It is now established that a good sex education has quantifiable results, called the hard outcomes, such as the reduction of unwanted pregnancies and adolescent abortions, the reduction of sexually transmitted infections, HIV, sexual abuse and cases of homophobia. At the same time there are also what are called soft outcomes, that are generalized improvements in social behavior, therefore difficult to measure, such as self-esteem, respect, sexual pleasure and so on.

Like any other type of education, the goal is to provide the necessary information so that, through constructive dialogue, teenagers can make free and informed decisions about their sexuality and their relationships.

Teachers are fundamental in this process because, regardless of their preparation, they often interface with questions that refer to sexuality, and it is necessary that they too have adequate training to answer. At the age of 3 already, children develop a sense of physical and sexual difference, so we must immediately approach the subject, to explain what you are like and have the right terminology to get to know yourself.

If we continue to talk about storks, flowers and bees, as they grow up, the children will have confused ideas and over the years they will discover the Internet and swear words, which for them will be "another thing” that they will perceive as new. Not knowing the right, technical words, they will associate a sense of shame and think it is better not to talk about it.

But by 3 years old? Yes, already from kindergarten you can undertake a path of education in affectivity. For example, Tabù e marmellata (Italian for Taboo and Jam) is a discloure project by Alice De Candia and Paola Bortoletto, which deals with sexuality and affectivity education in the world of childhood for parents, educators and teachers.

It is important that these teachings are given at school as socialization, the presence of other classmates brings out new doubts and shapes thoughts. Furthermore, it is not certain that the family is ready to emotionally manage certain contents, especially if they have not had a sexual education either, causing - again - embarrassment.

The baby boomers generation was also informed through the media. Let's take an example; adults today remember very well the photo of Lady Diana in which she shook hands with a boy with AIDS. Here, that image has become an icon, it was understandable to everyone and dispelled many prejudices; today is not enough. A contemporary media equivalent can be found again in the Sex Education series. Alix Fox, writer and sex educator, was involved to deal with some issues of sex education in the series, and in addition to giving advice to Gillian Anderson on how a sexologist should speak, she has also contributed to the writing of some parts of the series, for example in the scene dealing with HIV. It consists of 30 seconds of video that report in a simple, complete and accessible way the basics of what is important to know today, without pietism or rhetoric.

— no context sex education (@sexeducation) September 21, 2021

Although today's streaming series, and in general the media offer, are increasingly focused on sexual education (think of Gwyneth Paltrow's series, Sex, Love & Goop, or the 10 special episodes of the Italian Superquark+ with Piero Angela, or again the Sex, Uncut series on Prime Video) cannot be delegated to entertainment (and within this field we must also consider the role of pornography), because it would be reductive.

The World Health Organization speaks of CSE, a Comprehensive Sexual Education, which takes into consideration the physical, biological and health aspects of the sexual sphere, but also the emotional, personal and social components. Thus, UNESCO has drawn up an international technical guide on sexuality education, in which they draw up guidelines on how to adopt a global approach and responds to all the "excuses" raised to avoid education on sexuality.

The situation in Italy

Italy does not provide for the teaching of sex education as a compulsory subject, and in Europe Bulgaria, Cyprus, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania are also in the same situation. There have been more bills over the years which, however, have ended in thin air.

The first parliamentary act that mentions sex education is from 1967 and, eight years later, in 1975, the first bill was promoted by some parliamentarians of the Communist Party, entitled Initiatives for information on sexuality problems in the public school. Those were other times, Freud’s studies and Marcuse’s theories were cited in the law propositions, and there was talk of how "in Italy and in the other countries of the capitalist area, erotic messages were spread" in advertisements. In short, summing up, in the 70s the damages that could cause disinformation and hypocrisy were already understood, and the changes of the first sexual revolution and the interference of the Church were recognized. When it comes to this type of issue, the more conservative political opposition tends to postpone the problem, and it has recently happened with the ddl Zan with the rhetoric of "we have other more urgent problems to tackle".

Today Italy is "at 20 speeds", as Silvia Gola explained in Educating to sexuality on Il Tascabile, in the sense that, since there is no national law, each educational institution provides autonomously in terms of sex education independently, at the mercy of political currents and pressure from Catholic movements. It means that schools decide for themselves, maybe students do it in moments of self-management, inviting associations such as Virgin & Martyr, referring to regional initiatives (such as W L'Amore in Emilia Romagna), or relying on books and projects such as Making of Love.

The most recent proposal was presented on the 7th of May 2021 by Stefania Ascari, parliamentarian in the Justice and Anti-Mafia Commission, the first signatory of the “Red Code” law against gender violence. This is the Delegation to the Government for the introduction of the teaching of affective and sexual education in the first and second cycle of education as well as in university courses, that is, starting from elementary school and progressively developing in university courses. The bill also includes initiatives starting from kindergarten to raise awareness on issues of emotional and sexual education.

It is a bill that provides for the training of teachers in transversal teaching, in collaboration with families and with the technical support of expert psychologists, psychotherapists and sexologists. And if, after all the research and studies that Ascari cites, the government is still not convinced, we can also underline that public finance would cost nothing, but would only gain new informed and responsible citizens.

What should the sex education program in schools contain?

Let's try to compile a list of topics, by way of example and not exhaustive, that we think should be dealt with in a sex education program:

-

A section dedicated to pleasure (as well as masturbation), desire and respect, with a long discourse on consent;

-

Sexting, privacy and the sharing of intimate non-consensual material;

-

An analysis of the concept of sexual identity, with insights into gender identity, biological sex and orientation of attraction, which includes every spectrum and takes into account the concepts of binary and non-binary;

-

An overview of the anatomy that includes explanations on the menstrual cycle (and related issues, such as endometriosis), gestation and childbirth;

-

An analysis of the concept (or rather social construct) of virginity;

-

A parenthesis on abortion and self-determination, perhaps also stimulating a discussion on the binomial woman and mother;

-

Gender roles and their evolution over time, gender expression, expectations and nonconforming gender;

-

A presentation on sexually transmitted diseases and prevention tools, be it condoms, birth control rings or PrEP;

-

Heteronormativity and privilege;

-

An in-depth study on gender dysphoria, transition, deadname, pronouns and inclusive language;

-

Coming-out and outing;

-

A lesson dedicated to sex work, a nice vertical discourse on pornography, and that in all of this we focus on the notion of agency (and a further example could be gestational surrogacy).

-

A section on relational orientations (monogamy, polyamory, relational anarchy) and parentheses on jealousy;

-

Sexuality and disability;

-

Alternative sexuality (perhaps after reading Fabrizio Quattrini's Paraphilias and deviations).

[N.B. write us on Instagram if you think something is absolutely missing!]

Teaching sex education does not mean explaining the Kamasutra, nor imparting the “gender ideology”!!11!, nor does it mean instigating adolescents to compulsive promiscuity.

Framing sexuality as knowledge, treated through the lens of different school subjects, allows children and teenagers to have tools to understand the world around them, and above all it allows them to explore who they are and the relationships in which they will want to be involved. It’s time, now.