The beauty and the problem of glamorization illness

Is the Succubus Chic aesthetic the new Heroin Chic?

April 5th, 2023

Concepts of illness and beauty have long been intertwined in Western culture. From Elizabethan England to modern times, a thin but seemingly unbreakable thread links emaciated, suffering appearance, death and glamour, dictating aesthetic standards that are not only unattainable but potentially dangerous. A case in point? The characteristic chalk-white make-up with lead powder that Queen Elizabeth I applied to her face, neck and décolleté was used to hide the disfigurement caused by smallpox, but was also imitated by aristocratic women to create a pallor that symbolised their exalted status and contrasted with the tan of the lower classes who worked outdoors and in the elements.

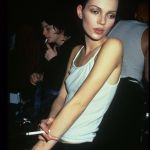

Fast forward to the heroin chic of the 1990s, when the height of collective desire was to look like Kate Moss. The most striking Polaroid from this period shows her in the background of a fashion show. She is wearing a simple white tank top and black trousers that accentuate her very thin profile, distinctive make-up that highlights her hollowed cheeks and sunken eyes, a cigarette between her fingers and a blank stare. This shot best encapsulates both the spectrum of the Sex, Drugs and Rock'n'Roll philosophy and the quintessence of heroin chic with its nihilistic vision of beauty, which many believe is making a strong comeback along with Y2K style and the glorification of extreme thinness. If thirty years ago the glorification of this aesthetic canon was through a blatant celebration of drug addiction and anorexia, in 2023 there is something much more thin-skinned and sinister about it, hiding behind wellness culture and a passion for cosmetics. Thus, size-0 models are displacing their mid- and plus-size counterparts from the catwalk and, at the same time, the years-long fight against body positivity; the Kardashians are adhering to restrictive diets and erasing the traces of the Brazilian butt lift; cheek fat removal surgeries are on the rise among celebrities; on TikTok, millions of views are turning Ozempic, a drug to cure type 2 diabetes, into a magical slimming wand that is also advertised in the Times Square underground station.

The latest beauty craze is called Ghoul Girl or Succubus Chic and is named after the figure of Succubus, a powerful female demon who uses her sexuality to appear in the dreams of her victims and kill them. The contemporary example matches the cholas and is inspired by Angelina Jolie's look in the 1990s: long black hair, very thin, almost invisible eyebrows, pale complexion, glazed look, high cheekbones and hollowed cheeks, without any trace of cheek fat. Commenting on the trend, she drew the parallel that many have noted between the images of Gabbriette Bechtel and Amelia Grey today and those of Kate Moss and Jaime King in their heroin-chic phase, writing: "Wednesday Addams if she grew up, got a job in Milan, and picked up a coke habit." In reality, the references to this new trend are much darker and further back in time. Pale skin, dark circles under the eyes and androgynous thinness were not only popular and desirable in the 1990s when they were associated with drug abuse, and they are not only today when we are slaves to plastic surgery and cosmetics to get them, but they were so in the 19th century.

Between 1780 and 1850, as Carolyn Day, associate professor of history at Furman University, reports in her book Consumptive Chic: a History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease, "there was an increasing aestheticisation of tuberculosis intertwined with female beauty." The Victorians, who included Charlotte Brontë, who called it "a flattering disease"," romanticised the disease that killed millions so much that they recreated its after-effects with make-up that was voted the standard of beauty: soft, transparent skin; fine, silky hair; sparkling or dilated eyes; rosy cheeks and red lips; a slim waist; round shoulders; and visible collarbones. "Health and activity were considered vulgar, sluggish and listless women with pale complexions were all the rage", and in the mid to late 19th century the lightening effects of tuberculosis were so sought after that women began swallowing wafers containing arsenic, washing themselves with ammonia and covering their bodies with white paint and poisonous glazes to try to lighten their complexions.

"In the 18th and 19th centuries, it was thought that the exterior revealed your interior character. The more attractive you were, the better a person you were. Today’s wellness ideals are also not correlated to actual health because anyone who doesn’t fit into the beauty standard is seen as unhealthy." Day explains and reminds us that not much has changed in 2023. Past and present chase each other, offering us snapshots that tell of the same notion of unhealthy beauty, now inescapably linked to a physique that is far more than elongated. A person with more voluptuous curves may be healthy, but always conveys the opposite message, because that is how we have become accustomed to beauty standards. Extreme thinness and a haggard, almost sick look always win. Just ask Gabriette, who, although always beautiful, talented and interesting, only became really successful after she became so thin that she became a kind of copy of Angelina Jolie in a dark 90s version. And what about Amelia Grey, who is almost a clone of Gabriette? The only thing that has changed are the tools we use to fit in. Real illness is no longer an option. Suffering has to be mimicked, worn on the face and body, but no one wants the major and minor complications and disabilities that come with chronic illness, nor do they want to deal with the people who suffer from it. Hollow cheeks, pallor, pronounced cheekbones and thin waists are achieved through a distorted idea of wellness that consists of restrictive and often absurd diets, wild cosmetic surgery, gruelling fitness sessions and buying mountains of cosmetics. In short, in 2023, holding on to a beauty that matches that of a tuberculosis patient in Victorian England means having a bulging wallet. The next time we suffer from seeing ourselves distant and ugly in comparison to Amelia, Kylie or Angelina, we should think for a moment. It is the beauty industry in general that needs to be re-examined and completely re-thought. Knowing the references of succubus chic will not change things, but maybe it will make us enjoy the gothic look without reproducing what is sick about it.