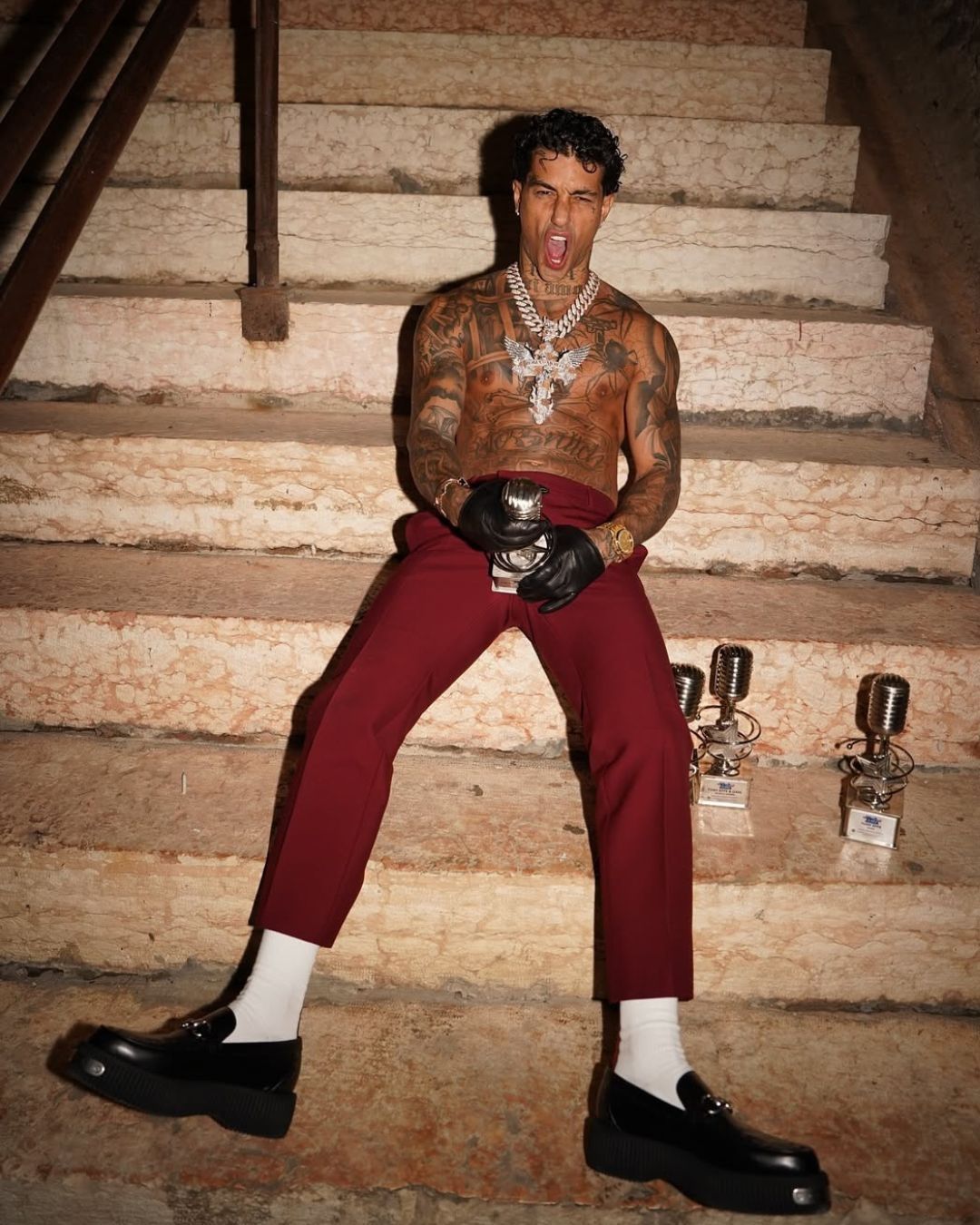

Is the sudden one from Tony Effe really censorship? Not exactly, but there is something to talk about

Tony Effe is on everyone's lips. And this time, at least, not because of his dissing with Fedez or his relationship with Taylor Mega, but for the misogyny in his songs, which cost him a spot on the stage at the New Year’s Eve concert in Rome, at the Circus Maximus. The decision was made by the event organizers following protests from the Campidoglio and the Differenza Donna association. Many of his colleagues have come to his defense, including Mahmood and Mara Sattei, who decided to withdraw from the event in solidarity. They weren’t the only ones, and now it seems the event is left without performers. User opinions are sharply divided: some find what they call a blatant censorship of an artist unacceptable, while others hope this marks a step toward cleansing Italian music of misogynistic themes and tropes, which are harmful to listeners, especially when it comes to very young and impressionable audiences.

Tony Effe and Roman New Year’s Eve: Is it really censorship?

Can this case really be called censorship? Not everyone is convinced. By definition, censorship is: "The control of communication by an authority that limits freedom of expression and access to information, with the stated intent of protecting social and political order." So, the questions to ask might be: Does freedom of expression exist when it comes to misogyny by famous and privileged men who—immersed in a patriarchal system—sing about women in an unflattering way, normalizing behaviors of slutshaming and objectification? And further: Can it really be called censorship if Tony Effe wins awards, tops charts, and participates in the Sanremo Festival, supported and defended by Carlo Conti himself? Finally: What threat to social and political order could be posed by a trap artist simply doing what trap artists do, dressed the part?

Are rap and trap causes or consequences?

The debate over the characteristic tropes of certain musical genres has been ongoing since their popularization, and we certainly won’t solve it here. It’s unclear whether the chicken or the egg came first—whether misogyny in music is a cause or direct consequence of certain attitudes toward women. The answer might be both. While it seems absurd to claim that patriarchy was invented by trap artists, it’s less far-fetched to suggest that Tony Effe’s fame and success are partly due to his alignment with patterns that are already winning—and, unfortunately, will continue to win for some time. Similarly, acknowledging that the way trap and rap discuss women reinforces a certain power dynamic, further validated through the music itself, doesn’t sound censorious but rather realistic and plausible. Have you ever read the comments left by teenage and preteen boys under videos of famous, curvy, or sensual girls? You’ll observe a linguistic and lexical flourishing that rivals Tony Effe and his peers. A coincidence?

The truth, as always, is that reality is much more complex and layered than the factions on social media or black-and-white Instagram story posts. Censorship is a serious matter (and words have precise meanings that shouldn’t be ignored). Even if we like Tony Effe, sometimes songs carry implications, influences, and impact that shouldn’t be underestimated precisely because they are far from activist. This doesn’t necessarily mean all representatives of a certain musical genre should be excluded from every music or entertainment event. On the contrary, reflecting on the relationships between things might be a good way to untangle certain knots. When and if patriarchy has been emptied and disempowered, we might finally understand what created it and what it created—and conduct a meticulous cleanup.