The history of the second feminist wave From the postwar period to the 80s

First-wave feminists claimed equality de jure, that is, they fought for recognizing the rights that men already enjoyed: the right to vote, political participation, an active role in the world of work, the recognition of being people before wives or mothers. In the immediate postwar period, following the fall of Fascism, veterans demanded that women be excluded from public and private employment, but feminists continued to fight for formal equality in the labour market. The 1950s were a period of transition and stalemate; many of the rules of the Italian Rocco Code still existed. In Italy, the real economic and social recovery took place in the 1960s, influenced by events in the United States. The baby boom, the spread of mass media and, yes, even the traditional return to family life are all preconditions for the second feminist wave.

Between media and reality

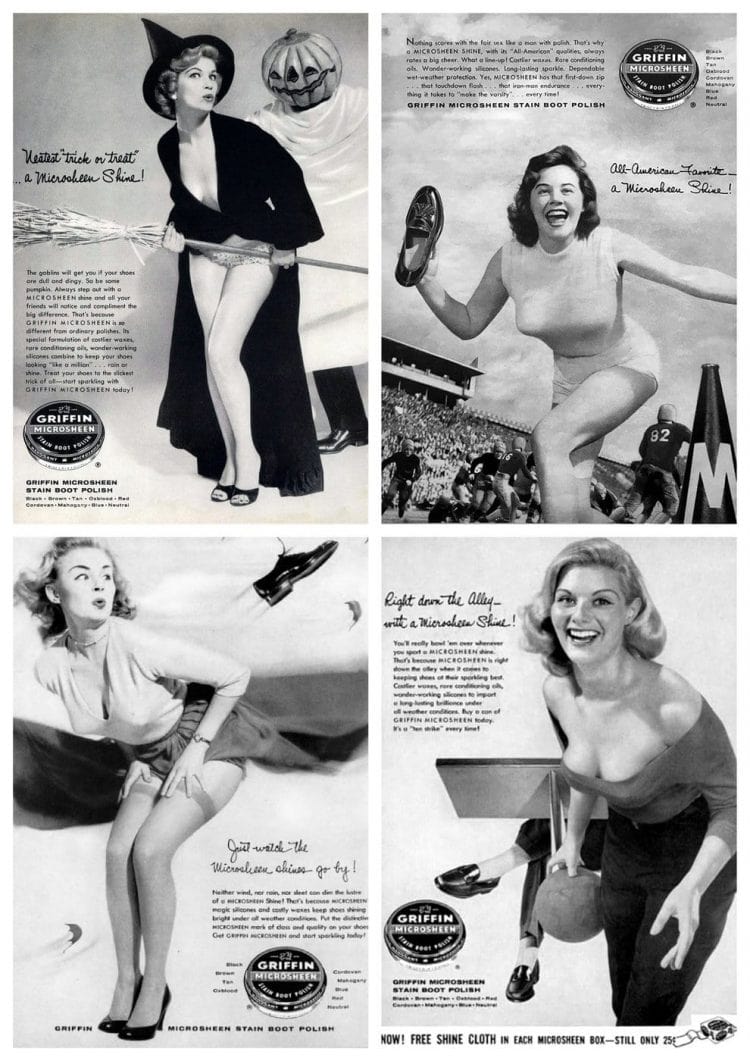

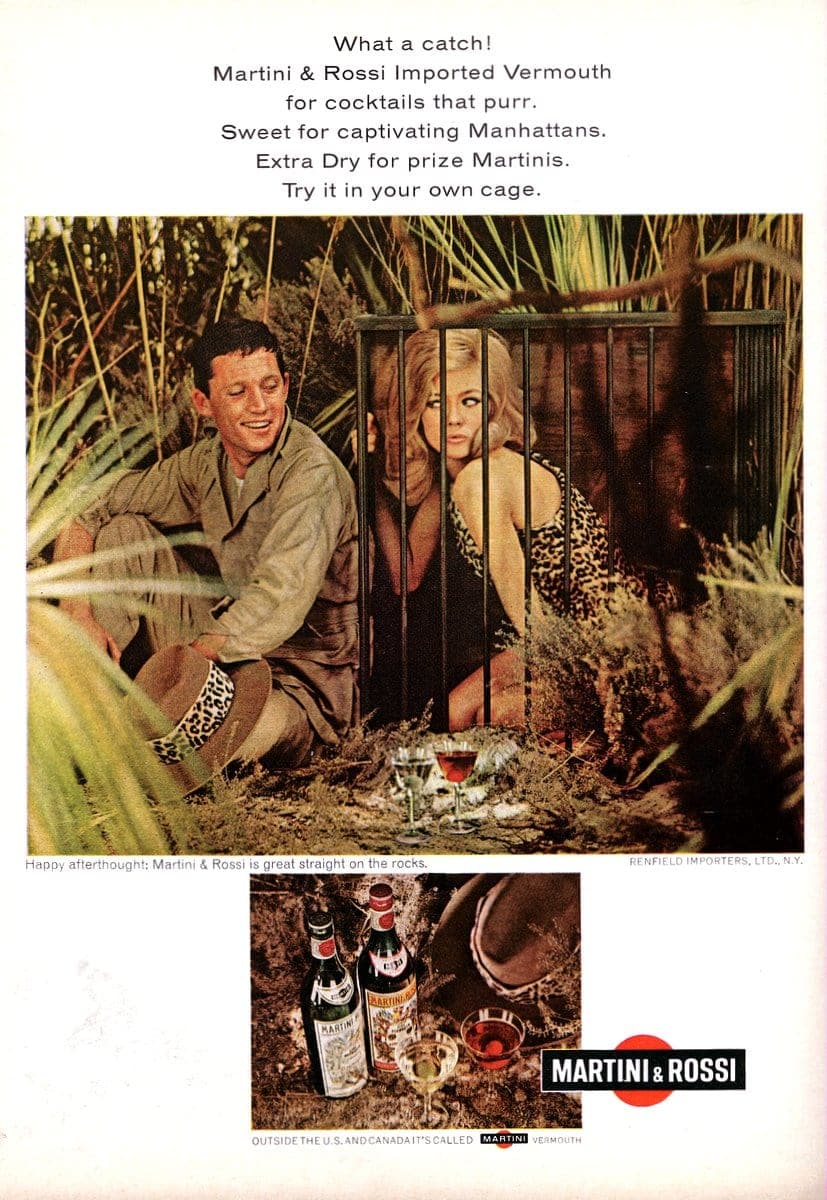

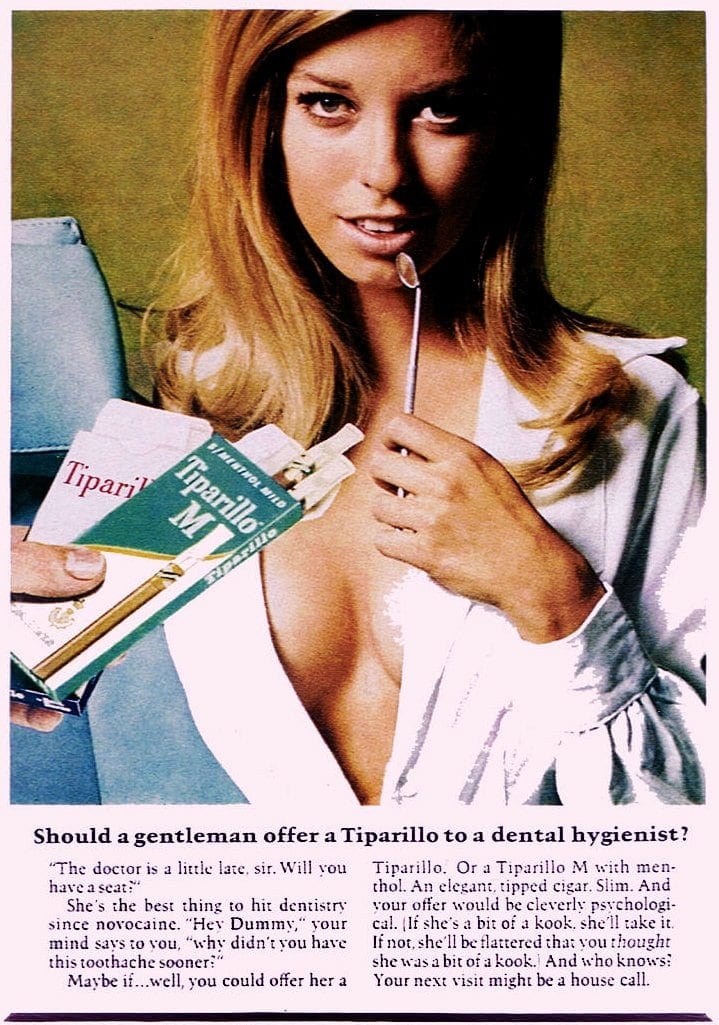

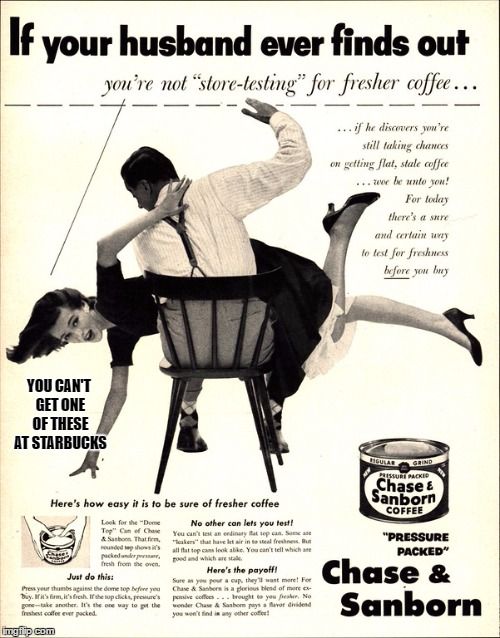

Although the equality claimed by liberalism had been achieved, important problems still remained, what we can call de facto. The domestic work and the care of the offspring were still totally dependent on the women, who found themselves doing a double job (private care work and the public sphere’s ones). The advertising images of those years mainly featured two female figures: the woman of the house, surrounded by new appliances, at the service of her husband; the modern woman, the pin-up, but always conditioned by the male gaze.

The dichotomy between real life and media representation was pointed out in 1959 by Gabriella Parca who, starting from 300 letters received from women from all over Italy, wrote Le Italiane si confessano (Italian Women Confess, from which the docufilm Le italiane e l’amore was based). The book highlighted the mismatch between the condition of suffering and ignorance of many women in the private sector (for example, for their first sexual experiences) and the advancement of Italian society towards modernity. Parca also denounced the prevarications, abuses and prejudices that Italian women were suffering within the home. From a similar context also comes Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique (1963), which distinguishes the real life of women (white ones, huh) from mainstream sweetened depictions in the media. Friedan analyzed what she calls the problem that has no name, which made women much more depressed and predisposed to the use of alcohol and psychotropic drugs. A cross-section of this type of society can be seen well in the TV series The Queen's Gambit, particularly in the characters of Beth's adoptive mother and her former high school mate. To trace the unspoken cause, Friedan conducts an investigation by interviewing former Smith College classmates and some housewives. The problem turns out to be precisely the mystique of femininity, that is a deception (which Friedan defines as a project of persuasion and conditioning) that leads women to remain closed in the roles of wives and mothers in domestic life, without undertaking a professional career. In the United States of the 60s: the average woman was getting married at twenty, a bank could refuse to issue her a credit card without her husband's signature and, if an employee became pregnant, it was perfectly legal to fire her. Second-wave feminism is thus intertwined with the student uprisings and with the Civil Rights Movement, driven by the huge success of Friedan's book. Women were asking for rights, respect and, simply, to stop being seen as containers for pregnancy and pieces of meat.

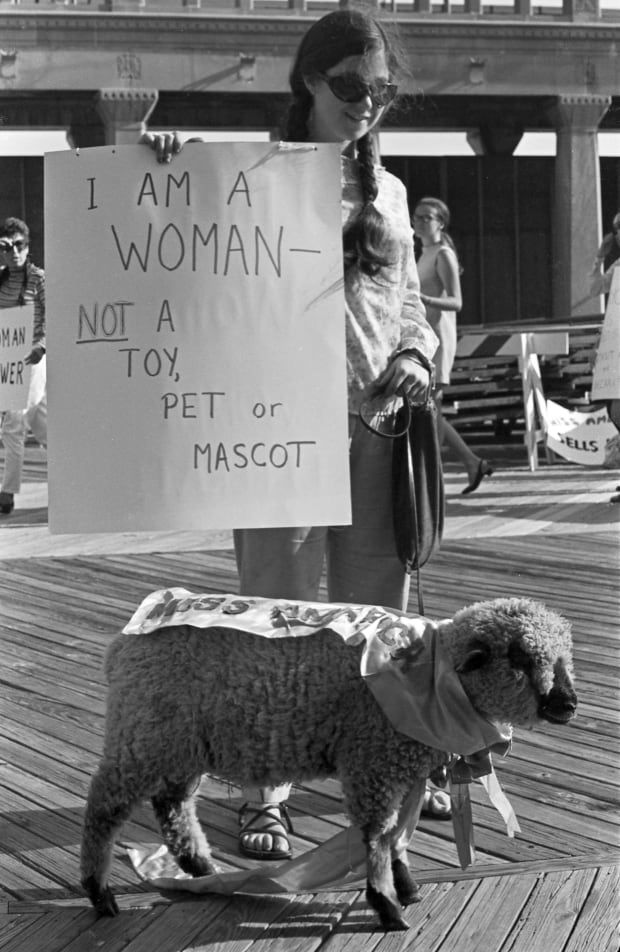

In the revolutionary climate of 1968, some American feminists protest against the Miss America contest and they install freedom trash cans, in which they throw away the "instruments of female torture": high heels, make-up, wigs, Playboy and Cosmopolitan magazines, and yes, bras too, but no, they didn't burn them, even if the myth still circulates today. In the United Kingdom in 1970 they stopped the Miss World contest screaming we are not beautiful, we are not ugly, we are angry!

Difference Theory’s fundamentals

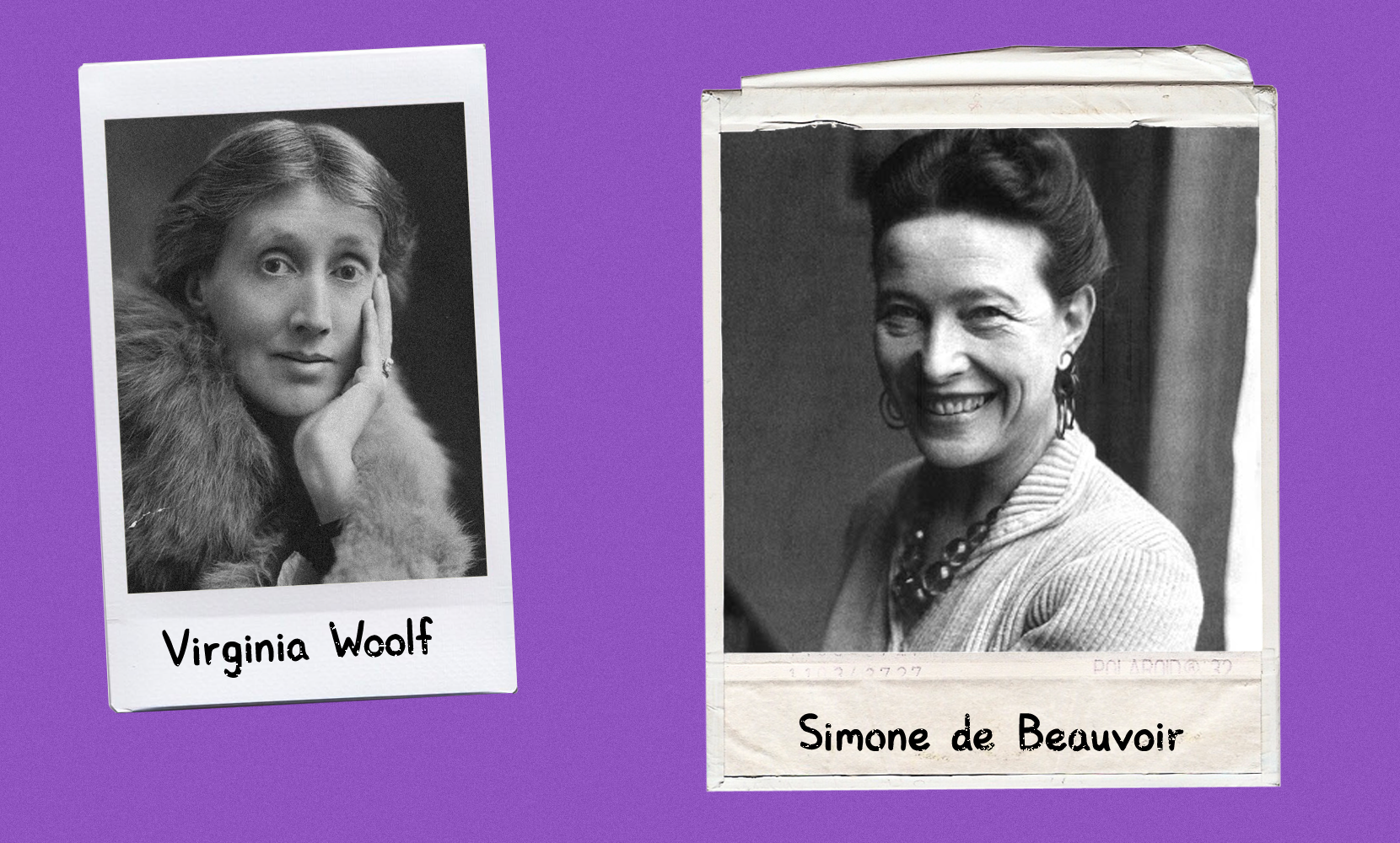

The media representations of the feminine reaffirmed a concept of inferiority, advertised in all forms and by all means, creating an underlying tension in the relationship with men. In this context, women begin a process of radicalization, through the formulation of discourse no longer centred on equality, but on the difference. It means that we go from “I want to be treated like a man” to “I want to have the same rights, but I also want my differences as a woman to be recognized”. It is not a light passage, far from it, in fact, it inaugurates the sexual difference theory. The first reasonings about difference, which founds the claims of this wave, can be found in two fundamental texts: Three Guineas by Virginia Woolf and The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir.

Three Guineas is an essay against the war (published in 1938 just before the outbreak of World War II) that starts from Woolf's experience as a woman, that is, marginalized and socially inferior. The woman, being other than the man, must regain possession of the differences and turn them into an advantage. We do not speak of equality, but of equal otherness. In The Second Sex (1949), instead, Simone de Beauvoir analyzes the subordinate condition of the woman who is considered, in fact, the second sex. On the contrary, the masculine has always been seen as the standard, the origin of language and the "neutral" point of view from which one looks at the world. De Beauvoir begins to investigate and deconstruct the "biological" characteristics that society has historically linked to the feminine. Feminine who must therefore accept the difference, but not the subordination. It is in this book that we find the famous phrase “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman". The text was so revolutionary that in 1956 it was included by the Vatican in the Index of Forbidden Books. In fact, these were "thorny" issues for the time, such as sexual freedom, pleasure and the right to abortion.

The thought of difference will then be articulated, especially in the linguistic dimension, by the French theory of Luce Irigaray, Hélène Cixous and Julia Kristeva, who followed the deconstructionist thought of the philosopher Jacques Derrida. In its simplest sense, the theory of sexual difference was to leverage a concept that is perhaps today considered, unjustly, banal: women are discriminated against precisely because they are women. Sex (we can now say gender too) is a category of oppression.

On this issue, on July 10, 1971, Gloria Steinem, considered the most influential voice of feminism in this wave, gave a speech at the foundation of the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC, founded with Betty Friedan, among the others). Address to the Women of America is remembered as one of the greatest speeches of the 20th century. Steinem speaks of a revolution that will lead to a true humanism, only when the categories of sex and race are abandoned. These in fact, “because they are easy, visible differences, have been the primary ways of organizing human beings into superior and inferior groups”. At the beginning of the video for Jennifer Lopez's song Ain't Your Mama (2016), you can hear an excerpt from the speech.

The uterus is mine and I manage it

Gloria Steinem is often credited with the quote If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament. Some attribute it to Florynce Kennedy, others to Germaine Greer; the most likely hypothesis is that the sentence was pronounced by an elderly Irish taxi driver. In any case, among the issues most dealt with by the feminist movement, there was certainly the right to abortion and contraception, followed by the demand for sexual liberation and the analysis of gender roles. The contraceptive pill was made available in the United States in 1961. In Italy, however, it was authorized six years later, but only for therapeutic purposes (for example to regularize the menstrual cycle). The Ministry of Health repealed the rules that prohibited its sale only in 1976. As for abortion, in Italy, it was legalized on May 22, 1978, with law 194, and then confirmed by the 1981 referendum. The battle to obtain the right to terminate the pregnancy was of fundamental importance for female self-determination.

In France, in particular, the Manifesto of the 343, published in 1971 in the Nouvel Observateur magazine and written by Simone de Beauvoir, caused a great sensation. It was a very strong stance: 343 women, in fact, publicly admitted that they had had an abortion (and in France, since the 1920s, those who aborted or procured an abortion were punished with sentences of up to six years). In addition to de Beauvoir herself, the signatories also included Monique Wittig, a great feminist theorist and writer, and actress Catherine Deneuve. The same initiative was revived in Germany with Wir haben abgetrieben! ("We had an abortion!”). In this way, the concept of motherhood passed from being a moral duty, based on a sort of biological destiny, to a pure choice of the woman. Feminists, radicals and liberals together, at the end of the Sixties, also moved by the student movements of '68, reformulated the discourse on marriage and motherhood, claiming the right to sexuality free from the purpose of procreation and free from the Christian-matrix’s prejudices. The first support groups and more conscious feminist associations were also born in these years, among the Italians we must undoubtedly remember the work done by Emma Bonino, Adele Faccio and Maria Adelaide Aglietta in CISA, the Sterilization and Abortion Information Center.

The personal is political

The reappropriation of bodies by women has mainly passed through self-awareness groups, feminist counselling centres and self-help courses of the late 1960s. They were all realities that tried to free women from falloscientific power, that is, a paternalistic state medicine centred on the needs of men. Basically, in self-awareness groups, women met to talk about their problems and to get to know each other and themselves (even from an anatomical point of view, with particular attention to the clitoris). The sharing of personal stories allowed each to recognize themselves in the experiences of the others, and to question the whole social context, but also the political and cultural one, in which they were inserted and from which they suffered oppression. The Italian term autocoscienza (self-awareness) was introduced by Carla Lonzi, founder of the Rivolta Femminile group and of the publishing house named Scritti di Rivolta Femminile, with which in 1970 she published for the first time Sputiamo su Hegel (Let’s Spit on Hegel), and then the following year La donna clitoridea e la donna vaginale (The Clitoridian Woman and the Vaginal Woman).

Self-awareness is a collective and individual process, which starts from each one, is expressed in the collective with the support of all and returns to the individual. The connection between the collective and the single person becomes the fundamental prerequisite for the famous slogan coined by the radical feminist Carol Hanisch in 1970: the personal is political. With self-awareness groups, women understand that their personal experiences, always considered "private", actually have their roots in the public. This means that if a woman suffers discrimination or general situations of suffering, it is not an isolated case, but a systemic and consequently political violence. The structures of the social, patriarchal and misogynistic context affect the private life of every woman.

This is how a great feminist consciousness is created which, spoiler, will not last long. Starting in the 1980s, the debate on sexuality will be deepened by feminists, discussing sex-work and pornography. On these issues, the feminist movement begins to split, and this moment is remembered as the sex war.

Tips:

- the documentary She's Beautiful When She's Angry (2014) and episode 7 of History 101 - Feminism (Netflix);

- the film Sex and the Single Girl (1964) inspired by the book of the same name by Helen Gurley Brown;

- Tv-series: The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel and Good Girls Revolt on Prime Video;

- books: Dalla parte delle bambine by Elena Gianini Belotti; Fear of Flying by Erica Jong.