The History of the Sex Wars

How feminism split because of porn

January 22nd, 2021

With the expression feminist sex wars, we refer to a series of debates that took place within the feminist movement between the late 70s and early 80s. The Sex Wars (also called Porn Wars) marked the turning point between the second feminist wave and the third (here you can find the story of the first). Since the 1970s, the main topic of discussion was sexuality; feminists talk about pornography, but also about sexual relationships and BDSM practices.

The sexual revolution had just ended, the Golden Age of Porn was beginning in the United States, and feminists were trying to put sexual relations in a theoretical framework. Journalist and activist Ellen Willis, for example, writes that sex is also subject to patriarchal mechanisms, that is, it replicates power dynamics that benefit male desires (to understand, the existence of the orgasm gap demonstrates that patriarchy also affects sex). This is already where radical feminism begins to creak. Two strands of thought begin to emerge, which will then take shape in two currents: anti-porn and pro-sex. Both were two radical ideological camps (with many internal problems) that started from very different assumptions. The pro-sex women screamed “sex work is work” to remove the stigma of prostitution, and at the same time the most famous anti-porn activist, Andrea Dworkin, wrote that “all sex is rape”, in all its forms. Not the best prerequisites for a debate.

The anti-porn front

Prominent figures: Andrea Dworkin, Catharine MacKinnon, Susan Brownmiller, Robin Morgan, Laura Lederer, Diana E. H. Russell, Adrienne Rich, Gloria Steinem, Susan Griffin, Kathleen Barry.

Let's talk about anti-porn. These radical feminists start from a total demonization of male sexuality because they think that sexuality is favoured by patriarchy. And it is from this idea that Andrea Dworkin started for the book Woman Hating (1974). The same theme of rape is also taken up in Susan Brownmiller's Against Her Will: Men, Women and Rape (1975), in which she talks about rape as the tool that all men use to intimidate and oppress women, and the latter two chapters are on pornography. In fact, porn is the main topic of criticism of anti-porn feminism, as you can guess from the name of the group. Robin Morgan in 1977 was able to synthesize the anti-porn positions by creating the mantra of the movement: pornography is the theory and rape is the practice.

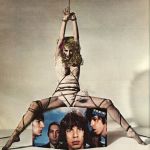

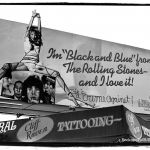

According to Dworkin, pornography harms women in both production and consumption. In production because the actresses who perform in the videos are humiliated, treated as objects. Brownmiller also says porn has turned women into adult toys (dehumanized objects to be used, abused, broken, and discarded). In consumption, however, because porn consumers internalize a violent and misogynistic representation. In fact, porn is made by male directors to make use of it - in fact - by other male viewers, therefore, according to anti-porn, it is incapable of representing female desire and sexuality. In any case, pornography is always considered a form of violence that illustrates the objectification of women by showing specific acts that, in hardcore porn, are real acts of torture. The WAVPM (Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media), a Californian feminist group, organized many protests and conferences between San Francisco and Los Angeles. In Hollywood the WAVPM manages to remove the billboard of the new Rolling Stones' album on Sunset Boulevard, which portrayed the model Anita Russell, tied with ropes, with her legs open, with the phrase I'm Black and Blue from the Rolling Stones' - and I love it. The ad copy was unhappy, and according to feminist groups, it conveyed a negative, almost celebratory message of violence against women, just like porn did.

The pro-sex front

Prominent figures: Ellen Willis, Gayle Rubin, Amber Hollibaugh, Betty Dodson, Dorothy Allison, Patrick Califia, Ruby Rich, Esther Newton, John D’Emilio, Jo Arnone, Sharon Thompson.

Feminism which, on the other hand, was in favour of pornography defined itself as pro-sex, because it was convinced that sexual freedom was a fundamental step in the struggle for the freedom of women (and all other people). Pro-sex women think that an a priori condemnation of male sexuality is incorrect: patriarchy negatively affects all sexual subjects, not only women, so we should not speak of a dominant male paradigm, but a male chauvinist one. The pro-sex also argue that we must rethink the figure of the sex worker who consciously chooses to do this job. They are not objects, but subjects. In addition, in porn there are not only women but also men, non-binary and queer in general, so they want to open the debate to all identities. These people are not only victims, but they know how to make autonomous, personal, and contextual choices. That's why pro-sex women see sex work (whether it's prostitution, posing for OnlyFans, or shooting porn) as any other type of work.

To describe itself this type of feminism used the expression that appeared in the essay Lust Horizons: Is the Women's Movement Pro-Sex? (1981), by journalist and activist Ellen Willis, who was among the first to criticize anti-porn feminism. Willis associated anti-porn claims with sexual puritanism, moral authoritarianism, and a threat to free speech, in short, the repression of sexuality. According to pro-sex, the production of pornographic material and its consumption are not harmful in themselves. Sure, they have their problems, but the solution is not to eliminate porn (which is a subversive cultural device), nor to remove women from porn. The basic idea was instead to involve women personally as producers, writers, and directors. And indeed so it was with the experience of Candice Vadala (known in the pornographic world as Candida Royalle), who in 1984 founded the first feminist production company. Vadala wanted to propose a type of pornography based on female desire, free from male-gaze, not oriented to the final "cum shot", but to the description of sexual activity in the broader context of women's emotional and social life. She ushered in the pornography of women for women. Femme Productions put pro-sex theories into practice that wanted to make porn a positive sexual model.

Two moments of confrontation

The first pivotal moment of these "wars" was the 1982 Barnard Conference on Sexuality, a lecture given in a private New York women's college. The theme was sexuality. Anti-porn feminists are excluded from the conference because, according to the organizing committee (largely pro-sex), they have already largely dominated the political and media discourse on sexuality and the purpose of the conference is to focus on a broader analysis of non-reproductive sexuality, not just about porn. Among the topics covered are also BDSM practices, which anti-porn saw as ritualized violence against women, while some lesbian feminists (from the Samois and Lesbian Sex Mafia groups) believed that BDSM was consistent with feminist principles because it was based on consent and respect. The anti-porn reacts by protesting outside the building, wearing t-shirts with writing on the front “For a feminist sexuality”, and on the back “against S/M”.

Photo by Morgan Gwenwald

The pro-sex positions on this debate can be summed up with questions posed by Ellen Willis in 1979: is there any objective criterion for healthy or satisfying sex, and if so what is it? Who decides which is a correct sexual practice and which is not? In this climate, the conference still manages to take place and the pro-sex "celebrate" the following day in the Lesbian Sex Mafia group.

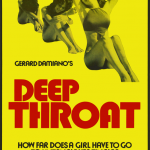

The other moment of confrontation comes with the Anti-Pornography Civil Rights Ordinance of 1984, a series of political events that began with the Golden Age of Porn, which is a period (from 1969 to 1984) in which pornographic films obtain the attention of the mainstream audience. These are the years that, according to an article by The New York Times, bring to light the "porno chic". The key example of this period is Deep Throat (1972), which creates a great stir. Linda Boreman, known as Lovelace, is pushed by her husband Chuck to participate in the film, becoming the first international porn star.

Linda then switches to the anti-porn lineup and is supported by the WAP, which before being the song of Cardi B ft. Megan Thee Stallion, in 1979 stood for Women Against Pornography. Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, the two most famous anti-porn feminists, begin to discuss the possibility of legal recourse for Linda. In essence, they believed it was possible to view porn as a violation of women's civil rights, a form of sex discrimination, and an abuse of human rights. In this way, those who had been harmed (more or less directly) by pornography could ask for damages to those who produced or distributed pornographic material. They then try to draft a local ordinance. Pro-sex feminists create the group named FACT (Feminist Against Censorship Task Force). In fact, the ordinance would have transformed all erotic/sexual material into a potential legal liability for the seller, and in this way it would no longer be disseminated, establishing a de facto censorship.

In 1985 the Federal Court ruled that, according to the First Amendment, the order is unconstitutional, so it does not pass. The anti-porn movement is weakened because, in this struggle, it sided with Reagan's conservative wing and with Christians (the role of religious associations can still be understood today with the December scandal on Pornhub).

The rift leading to the Third Wave

Many people believe that sex wars were just intellectual debates between New York feminists. Actually, they should be seen as a moment of far-reaching political and academic scope. Sexuality, for example, was a topic that had always been used only by men and that second-wave feminism had defined as an instrument of oppression. With sex wars, on the other hand, the arguments about sexuality become specific to women. The debate has raised problems that are still unresolved today, indeed, we can say that they have become even more complicated. In short, the sex-wars have led to a split in lesbian and radical feminism that has fragmented the feminist movement until it reaches the Third Wave.

Feminist critic Teresa De Lauretis sees sex wars as the reflection of a nascent new wave that inherently embodies difference, and therefore can include conflicting and competing drives. We no longer speak of that thought of the difference between masculine and feminine, but differences within the same group of women and feminists. The third-wave writings thus promote personal and individualized views on gender issues and focused on sex wars, such as prostitution, porn, and sadomasochism. As radical feminists understood during the years of the sexual revolution: sex is a place of power and vulnerability.

.webp)