The history of the third feminist wave From the 1990s to the early 2000s

With the expression "third-wave feminism" we refer to a period, which goes from the beginning of the 90s to about 2010, in which new currents and theories emerge within the movement. Indeed, it would be more correct to say that a feminist movement actually no longer exists, because it has been replaced by many different feminisms. In the second wave, the main topic of discussion was the difference between man and woman, between masculine and feminine, but then, with the first splits of sex-wars, feminism focuses on the analysis of its internal differences.

In the essay Understanding Third Wave Feminisms Elizabeth Evans, a researcher at the Goldsmith University of London, writes that "the confusion surrounding what constitutes third-wave feminism is in some respects its defining feature". In fact, between postmodern feminism, transfeminism, ecofeminism, cyberfeminism, girly feminism and so on one could get lost. The feminists of the nineties understood that it is no longer possible to speak of "Woman", simply because the world is different in every part and therefore every social, cultural, political, geographical context, etc. influences and determines the feminist experience of each person. With the third wave, space is given to the various types of women: black feminism claims its peculiarities, and so do Indian feminism, Latin, Marxist, lesbian, and so on.

Intersectionality theory

In 1989, jurist Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to discuss the discrimination and violence experienced by black North American women in the 1970s.

It all stems from a trial in which five workers - unemployed - accused General Motors of racial and sexual discrimination, claiming to have been fired for being black women. Before the Civil Rights Act (1964), General Motors had never hired a black woman. In the Seventies, in reaction to the economic crisis, they began to reduce staff, protecting employees with more seniority. It goes without saying that black female workers were the first to be fired, while most of the white women and black men remained. A legal term was needed that combined the two experiences of discrimination, and so intersectionality responds to the need to intersect gender with other categories, such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, or disability. People experience multiple levels of intertwined oppression. In fact, social categories are at the basis of discrimination, and it is here that the debate on the concept of privilege - already discussed by postcolonial studies or by Afro-American feminism - opens up. The theory of intersectionality (which, however, has received interesting criticism) has allowed us to think about the differences in the feminist movement, and about the solid internal divisions.

Where does the third wave come from and what is it

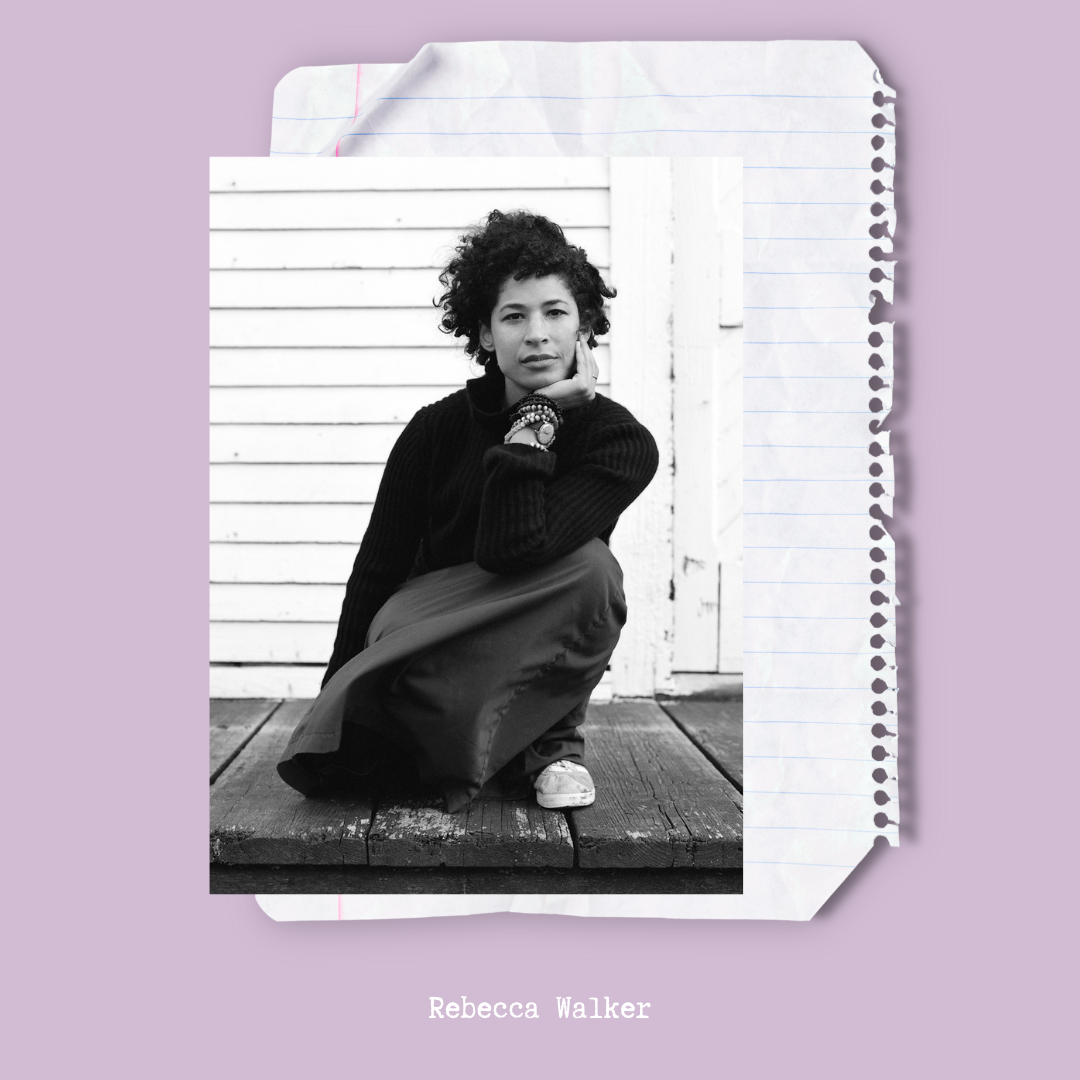

Rebecca Walker is an American writer and activist who is considered the first person to have spoken explicitly of the third wave because in 1992 in an article in Ms. magazine she wrote: I am the Third Wave. Actually, a year earlier, in 1991, in the book The Beauty Myth Naomi Wolf had written that there was a need for a third feminist wave. The book, a feminist bestseller, is a criticism of the aesthetic standards imposed by society that oppress women.

Walker was probably chosen as the "founder", or at least as a reference figure, as a black feminist daughter of a great activist and writer, Alice Walker. Wolf, on the other hand, has repeatedly been the focus of discussions in the feminist academic landscape, and over the years has promoted numerous conspiracy theories. In any case, Rebecca Walker theoretically framed the third wave. If second-wave feminism was born as a continuation of the women's rights movement (suffragettes &co.) in which no one had mentioned the word "wave" because there was no feminist consciousness, the third wave is formed instead starting from a type of feminism declared and already trained (i.e. Gloria Steinem). The third wave is therefore a new feminist movement in itself, born in its time to fight and face the issues that arose and developed in those years. Walker explains that the second focused on a specific type of woman: white, cis, middle-class; while the third opens up to a variety of women from different social backgrounds, it is in fact intersectional feminism.

Objections to the wave's construct

When the differences were recognized, some scholars such as Shira Tarrant or Linda Nicholson criticized the concept of "wave".

Whenever we talk about waves, in fact, we refer to the developments of the feminist movement that took place essentially in the United States, highlighting particular moments and certain ideas. In essence, that of the waves is not feminism, but mainstream or white feminism, ignoring the history of political issues in the rest of the world. Furthermore, the metaphor of the wave suggests that there are peak moments and moments of stalling or distancing, underestimating the importance of the progress made between the periods. Some feminists have therefore said that it no longer makes sense to speak of waves but of individual stories of different feminisms, in time and space.

The context

The third wave was therefore born in the nineties with the succession of two emblematic events. The first is the televised testimony of Anita Faye Hill, a lawyer and university professor, in which she sued Judge Clarence Thomas - a candidate for the Supreme Court - of sexual harassment. Hill testified before a Senate judicial committee made up of all white men. The votes were resolved with 52 votes in favour and 48 against, so Thomas was appointed to the Supreme Court.

The case had great media coverage and public opinion was divided between those who supported the judge and those who, instead, believed in Anita (so much so that the slogan I believe you Anita was born, then also taken up with the #MeToo). Not so incidentally, Walker's article on the third-wave stems from a commentary on Hill's story.

The second event coincides with the start of the Riot Grrrl movement in Olympia (Washington). Until then, punk was a male territory, but several feminist activists began to create zines and form bands - such as Bratmobile, 7 Year Bitch, or Heavens to Betsy, carving out an underground alternative and starting to wear dr. Martens. In those years Kathleen Hanna, singer of Bikini Kill, worked on the zine on which the Riot Grrrl manifesto appeared, which took sides against the society that says that saying "Girl" is equivalent to Dumb, Bad, Weak.

During their concerts, the Bikini Kill screamed Girls to the front! to invite girls to claim their own space, and then do it in society as well. Music in recent years has particularly influenced the feminist movement and spreads the concept of empowerment. One of the Bikini Kill zines was called Girl Power, and in the late 1990s, with the rise of the Spice Girls, that expression became a mainstream pop slogan.

And this is also the beginning of another feminism called girly or lipstick feminism, which consolidates the narrative of empowerment and allows that in the context of the third wave both the hijab and a crop top can be considered symbols of resistance to objectification, and forms of personal expression.

The themes of the Third-wave

The main argument of the third wave is provided by queer theory, born from the work of Teresa de Lauretis in 1991 and reinforced by the thinking of Judith Butler, philosopher and gender theorist. In the Nineties, the homosexual community regained possession of the "queer" label, which since 1922 was used as a derogatory term, of hate speech that intertwined the concepts of strangeness, disease, and homosexuality. The queer theory proposes an overcoming of binary categories (male/female, heterosexual/homosexual) by multiplying the discourse of differences: it's the basis of the current LGBTQIAPK+ community. The reappropriation of a term of hatred can also be found in another sense with slut walks, demonstrations in which women protested against the rhetoric of "how did you dress at that moment?" aimed practically at justifying rape.

The theme of violence against women is still strong, in all forms: rape, domestic violence, harassment, abuse, genital mutilation, and reproductive rights. V-Day was also born, a symbolic day to talk about these acts of violence, thanks to Eve Ensler's The Monologues of the Vagina, written in 1996. The book is based on interviews with a heterogeneous group of more than two hundred women and talks about all that which concerns the vagina, "in times of joy and sorrow".

The debate on sexuality, sex work, and porn continues. The pop feminist magazine Bitch is born, focusing on mainstream media representation (the release of Thelma & Louise had aroused a lot of controversies). In the early 2000s, the feminist movement expands, there is the Internet, which means that e-zines and blogs (such as Feministing by Jessica and Vanessa Valenti) connect people all over the world, allowing feminist demands to be disseminated in a new way. What is considered the "fourth wave" arises from here. In part from the theories of Donna Haraway and Rosi Braidotti in part from the episodes of Sex and the City.