Is there a fourth wave of feminism? Between #MeToo and "We Should All Be Feminists" T-shirts, activism has become digital

Feminism is historically classified into three "waves" (first, second and third) which, however, can't fully reflect all the differences. We can understand it just by the temporal division with which each wave is circumscribed, which follows the developments of the US feminist movement: not the best premise for providing a global vision of a multicultural and intersectional social movement. Thus in recent years, the discourse on great Feminism has shifted to the individual stories of the different existing feminism. In this context, does it make sense to speak of a fourth feminist wave? Yes and no, maybe no. In fact, we are already starting from a distorted and unbalanced perspective that has always provided a partial representation of events. This focus on "Western" events has created the rhetoric of «today feminism is no longer needed» because it is believed that all rights - at least the «most important» ones - have been recognized as an outdated ideology that in the common imagination coincides for good or bad with the second wave, or - said as if we were boomer - to angry hairy women who burn bras and hate men. But at the same time, there is talk of a fourth wave or at least every day we deal with an issue from a point of view that we consider feminist.

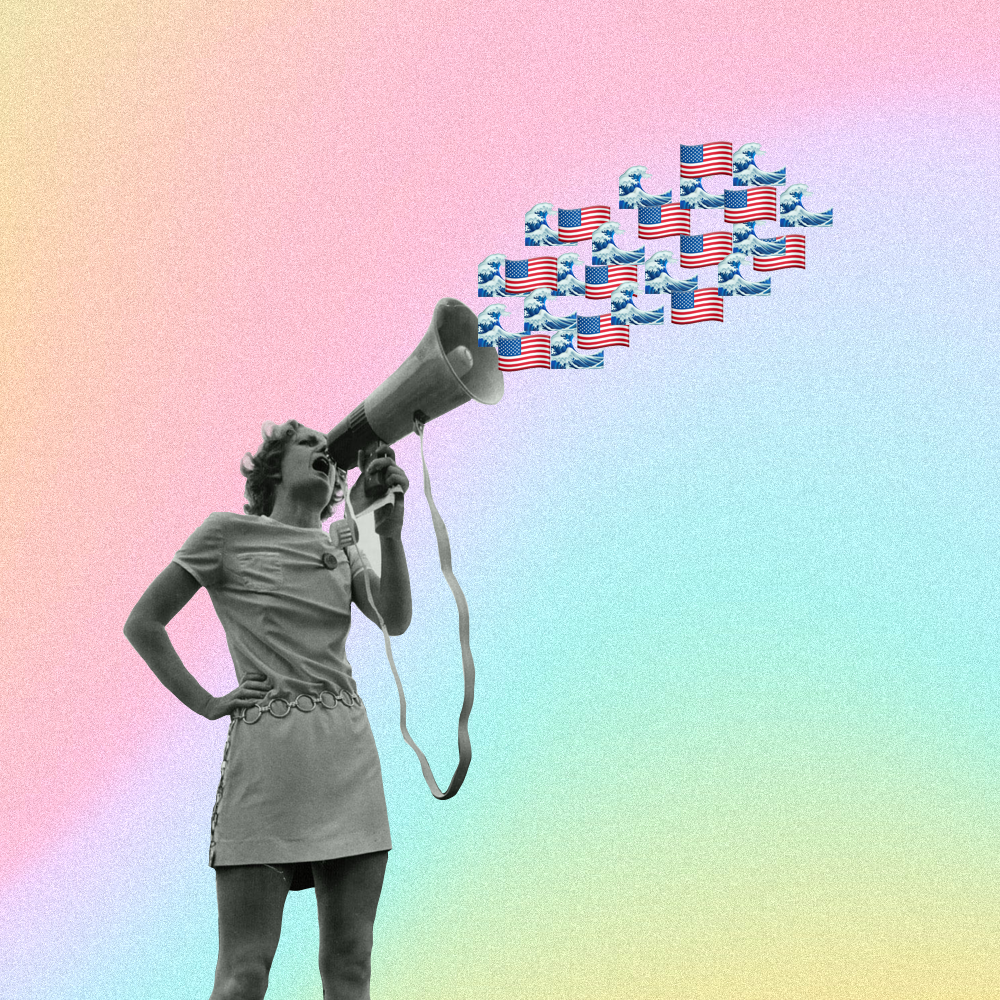

There is controversy over an article in some clickbait-slave newspapers, there are protests against the ridiculous comments of some politicians and large online awareness campaigns. Many feminist themes have entered every day speeches, it is a fact, it is also undeniable that they still reflect a Western positioning. The conditions of disparity in the world are characterized by individual contexts and also by global dynamics, so it can be functional to speak of the fourth wave on a macro level. We appeal to the concept of "strategic essentialism", proposed by the postcolonial philosophy Gayatri Spivak, which - explained in a reductive but easy way - means that several people can speak in the name of a single group to emphasize a common cause. A straight black woman, a white lesbian, and a trans man are people aware of their differences, but they can politically affirm a unique identity, as in the case of DDL Zan. Using the expression "feminist fourth wave" highlights a widespread movement that is already present in effect.

Origins and characteristics of the fourth wave

In 2011 Jennifer Baumgardner published F'em! Goo Goo, Gaga, and Some Thoughts on Balls, a collection of essays, articles, and interviews that can sum up the starting point. In fact, we find a great variety of themes, from breastfeeding to Björk, between Riot Grrrl and intersectional activism. It fully reflects the third wave. In the last chapter, Is there a fourth wave? If so, does it matter?, Baumgardner talks about a "tech-savvy and gender-sophisticated" generation that posts lengthy blog articles and tweets for a broad spectrum of gender identities. Among the reference projects, we find the Feministing blog created in 2004 by Jessica and Vanessa Valenti (who left it in the hands of "younger" feminists in 2011) and The Everyday Sexism campaign created in 2012 by Laura Bates. There was - and still is -a website that collected stories of daily sexism from all over the world, from catcalling to discrimination in the workplace, which converged two years later in a book: hundreds of ordinary stories that people can easily identify with. Today it would not seem like anything new, but it's there that the first hashtags were born with the aim of creating an alternative online form of solidarity, with a global character (from #BringBackOurGirls to #HeForShe).

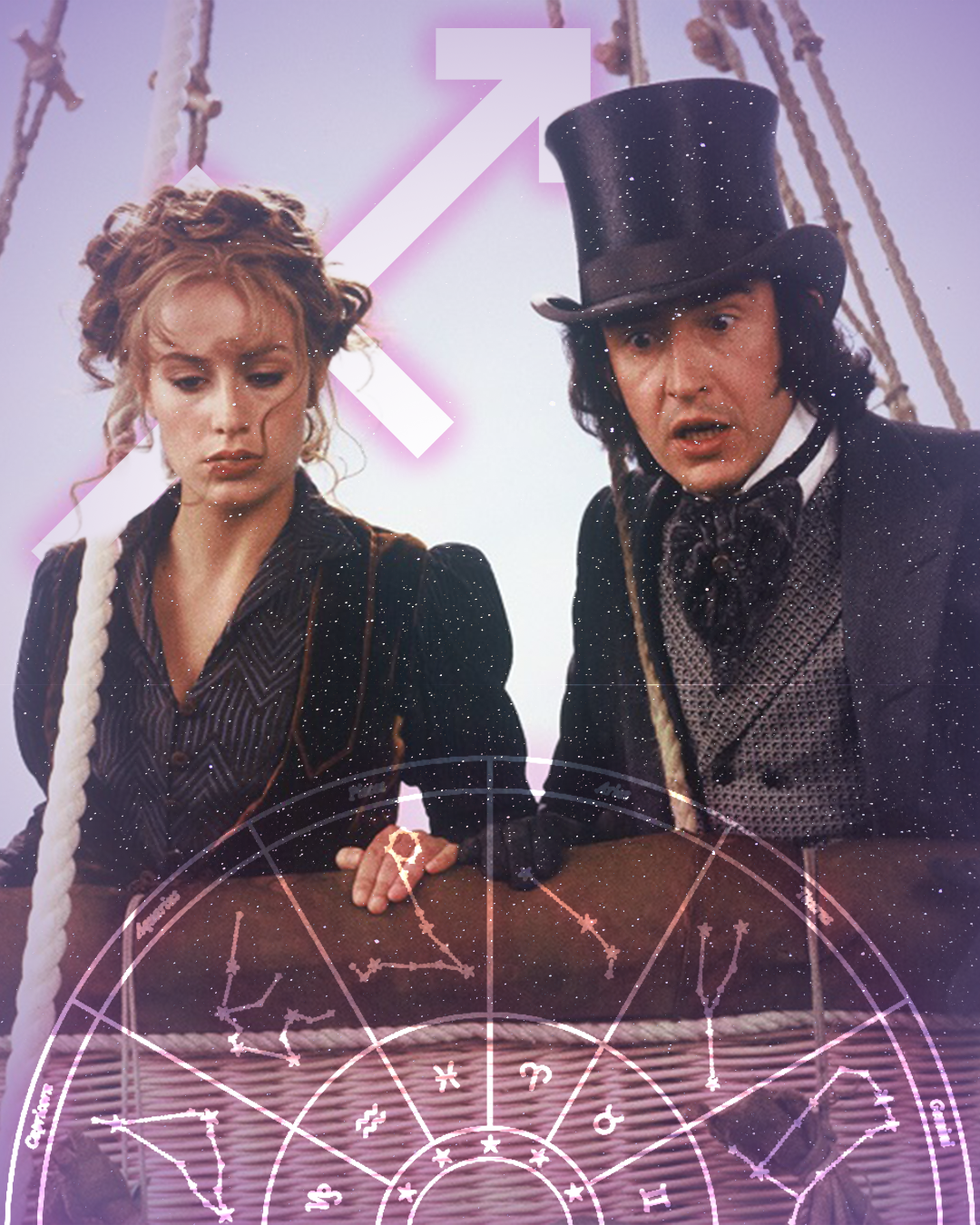

Obviously, there was no lack of criticism, such as that of the Australian radical feminist Germaine Greer (second-wave intellectual repeatedly accused of transphobia) who in an article had commented on the project saying that "simply coughing up outrage into a blog will get us nowhere”. But according to the English journalist Kira Cochrane, it's precise with The Everyday Sexism that the fourth feminist wave clearly begins: a movement defined by technology, which through the possibilities of the network becomes popular (even pop), and fights with pragmatism and humour for the inclusiveness. An example of the fourth wave is Beyoncé's performance in August 2014 on the MTV VMAs stage, where she sang Flawless with the FEMINIST lettering behind her. The song, in fact, includes an extract from the speech We Should All Be Feminists by the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and has made it possible to reach people who probably would never have read a text by Adichie.

From #MeToo onwards: the themes

Every year Merriam-Webster, US publisher of the famous dictionary, decrees the word most searched and used in public conversations: in 2017 it was "feminism". The search percentage had grown by 70%, in particular with two peaks: in late January, after Donald Trump's inauguration in the White House with the Washington Women's March, and in October with the explosion of the Weinstein scandal and the #MeToo.

If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet. pic.twitter.com/k2oeCiUf9n

— Alyssa Milano (@Alyssa_Milano) October 15, 2017

The expression Me Too comes from an African-American activist, Tarana Burke, who in 2006 used it as a slogan to arouse empathy and support for black women and girls who had suffered harassment. Eleven years later, actress Alyssa Milano used the hashtag on Twitter to entice other women to report and expose themselves after the accusations against Harvey Weinstein. #MeToo on the one hand brought visibility to a movement giving it worldwide resonance, on the other hand, it also appropriated a practice of self-awareness of a group of women who were not those represented. The expression doesn't belong to white women in Hollywood, but it fits into mainstream discourse in an attempt to draw attention to the pervasiveness of sexual abuse in an intersectional way.

Fourth-wave feminism is based precisely on intersectionality, on freedom of choice (in reproductive justice as in sex-work), on an analysis of media representation and online dynamics. It's a movement open to everyone that should advocate a transnational and anti-capitalist feminist practice. The arguments of the fourth wave are essentially the same as those of the third, but they have a different connotation given even only trivially by social and technological variations. The body-positive, sex-positive, and "Free The Nipple" movements are re-proposed, we openly talk about sex and pornography, between sexual education and sex work, but rather than doing it in seminars and conferences we move to Tik Tok and direct on Instagram, even if some Slut Walks are still there. From here, for example, a whole new discourse on self-objectification has also developed, which by some feminists is considered a form of devaluation, for others, it is a positive reappropriation of one's body, still, others consider it a legitimate form of exposure of oneself according to one's desires.

Sexuality is also treated in terms of violence, abuse and rape, and an attempt is made to analyze them also in relation to other identities, not only in the "women" category. Each theme is also expressed in the geographical context in which it is treated by Millennials and Gen Z: it's the politics of location by Adrienne Rich, for which a place on the map is also a place in history. Each subject is located in a hic et nunc and, therefore, produces a knowledge that is always different. There is talk about Islamic feminism, cultural appropriation, social problems according to an approach that re-personalizes politics, and takes sides in favour of all marginalized subjects.

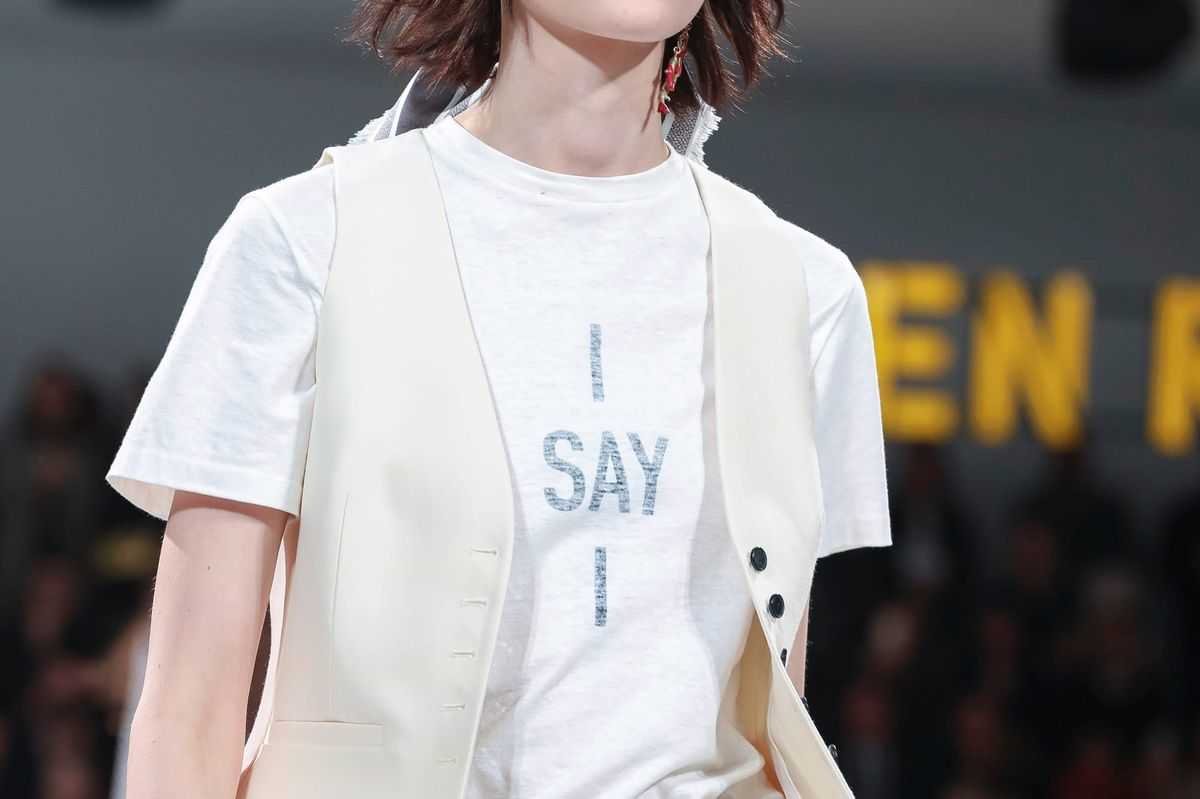

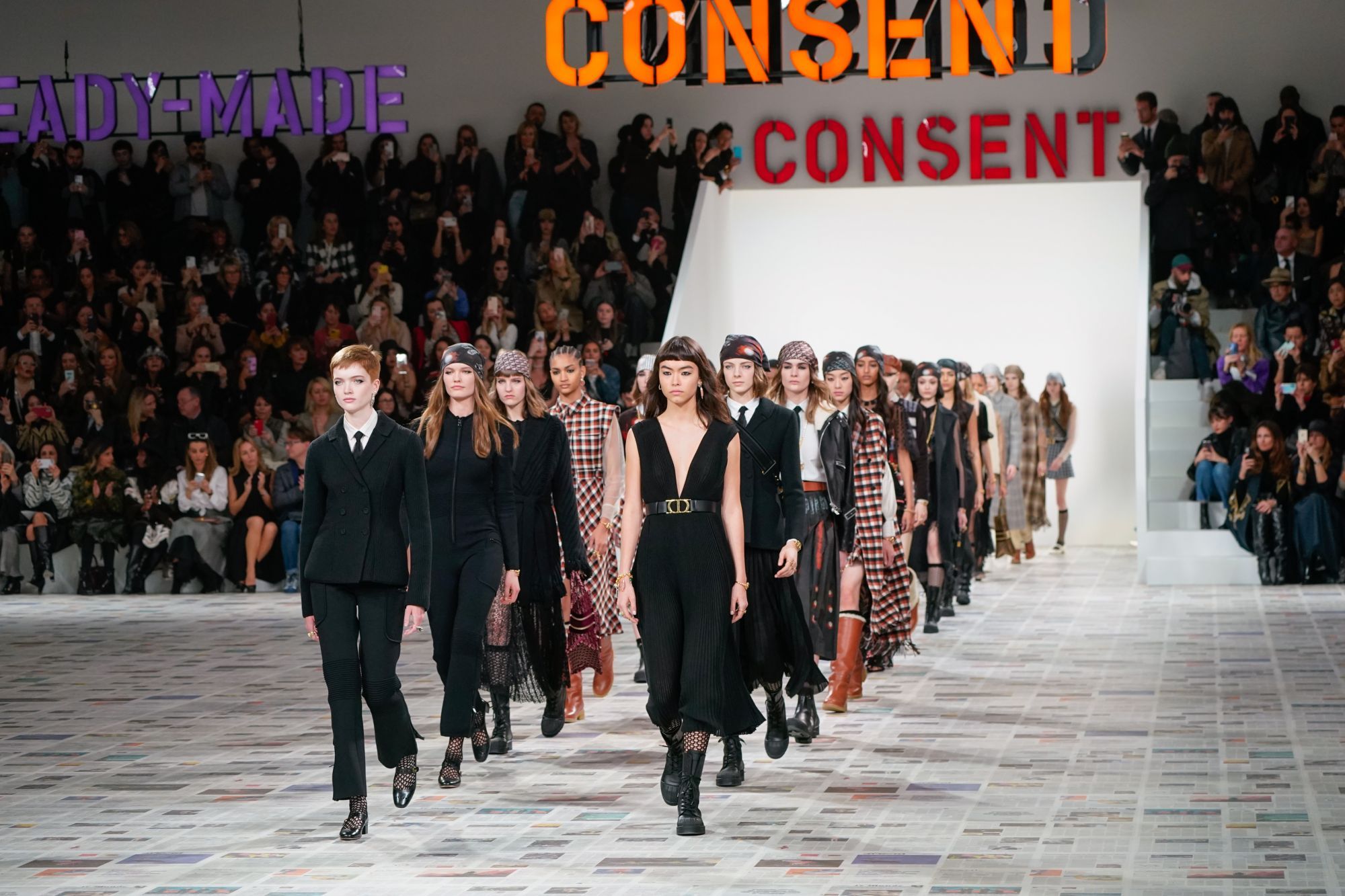

Pop culture, online and marketplace feminism

To find signs of political influence and activism, feminism no longer looks only at traditional institutions (conferences, universities, protests, marches and so on), but has carved out a large space on social media, offering anyone the opportunity to make the voice heard all over the world - as long as there is good Wi-Fi. This has brought a lot of attention to feminist claims, but it has also led to new marketing opportunities. This is what Andi Zeisler, the founder of Bitch, called marketplace feminism, that is all those practices of commercial co-optation that have emptied feminism of its political meaning and that have allowed celebrities, brands and editorial projects to appropriate it for advertising purposes. Returning to Beyoncé's example, in 2016 Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri presented a We Should All Be Feminists t-shirt and more and more people wondered if a $710 shirt could be considered feminist. In that case, it has to be said, a percentage of the sales was donated to The Clara Lionel Foundation, a non-profit organization founded by Rihanna in 2012. From here, in We Were Feminists Once (2016), Zeisler analyzed the social repercussions of this feminism that intersects with pop culture, creating an approach that is decontextualized, controversial and in search of clickbait.

If previously TV shows, films, documentaries and books were produced, now feminism is sold in a non-textual form: lines of underwear, toys and even some energy drinks define themselves as feminists. The counterpart to pinkwashing is online activism, with its strengths (one of all the great work of divulgation) and its weaknesses, such as having to always take sides immediately on every controversy, without dealing in-depth with the topics. The confusion given by the many feminist "battles" is also reflected on a theoretical level, so especially in Italy it's not possible to clearly outline a common program, and the concrete implications do not even have time to materialize, because they are lost in Instagram stories.